Sitting on the stairs at the entrance of a building – shy look, short black hair, a tired tone of voice, slim and brown skin- Daniel is wearing a red helmet and vest and next to him a black bike he uses at work every day.

Daniel, 25, who preferred not to give me his complete name due to his immigration status, is one of the millions of essential undocumented workers throughout the U.S. who distributed meals to homes during the COVID-19 lockdown from March to July 2020. Despite Daniel’s personal sacrifice and service, essential workers like him have been for the most part excluded from COVID-19 relief, and face an uncertain future.

“People who have less power get less voice and less protection,” said Jessica Neuwirth, lawyer and Director of the Human Rights Programs at the Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College. “It has always been wrong but especially wrong when you are dealing with a life/death pandemic.”

Concerning the COVID-19 and the Humans Rights of Immigrants guidance and U.S. government disposal, Neuwirth says, “We are out of step in many ways with the global community and international norms. The U.S. has always promoted itself as a country that believes in the rule of law and promotes global agreement.” But, she continues, “The U.S. does not always practice what they preach.”

Italy gave temporary work permits to 220,000 undocumented workers who worked primarily in the agriculture industry and domestic workers as part of a stimulus package, providing survival pathways.

The same cannot be said of the U.S. where at least 11 percent of agricultural essential workers are undocumented immigrants, according to FWD.us, a pro-immigration lobbying group.

During the pandemic lockdown, the U.S government implemented the CARES act as an economic response to the pandemic that included stimulus checks, an extension of employment benefits, and support to small businesses; however, undocumented immigrants like Daniel were not included.

“I got COVID-19 while working,” said Daniel in Spanish. “I brought food to people that I don’t know, and some of them were sick with the COVID-19 virus.” Daniel lost his sense of smell, fever, and all the COVID-19 symptoms, but he did not stop working. “There was no other way; there were restaurants that fired those who did not want to work. The chef did not want to return to work for the safety of his family, and he was a resident, I am just a deliveryman and undocumented,” he said.

The United Nations Commission on Human Rights sent guidelines on protecting immigrants during the height of the pandemic, saying everyone, including migrants, regardless of their immigration status, must be considered an integral part of any effective COVID-19 public health and recovery response. In addition, the Commission emphasized, “social protection measures should be available and accessible to migrant workers and their families since they are likely to be in precarious working conditions and disproportionately affected by unemployment or reduced employment as a result of the pandemic.”

Only two states provided economic relief to undocumented people, California and New York. Last year, California contributed $75 million, plus a $50 million fund from private philanthropies as a disaster relief assistance for undocumented people. In April 2021, New York approved the excluded workers fund for $2.1 billion as part of the state’s budget. Assemblywoman Carmen de la Rosa led the initiative with Senator Jessica Ramos, law firms, and a coalition endorsed by nonprofit organizations and institutions. “We stopped the traffic in Manhattan and Brooklyn bridges and did manifestations in the New York State capitol and city hall to make known the pledges of the undocumented community,” Assemblywoman Carmen De La Rosa said.

The excluded workers fund is the only one in the Nation. “There is a problem of racism to give funds for undocumented workers,” said De La Rosa. “These workers are not asking for charity; they are asking for a benefit based on their contribution to their work.”

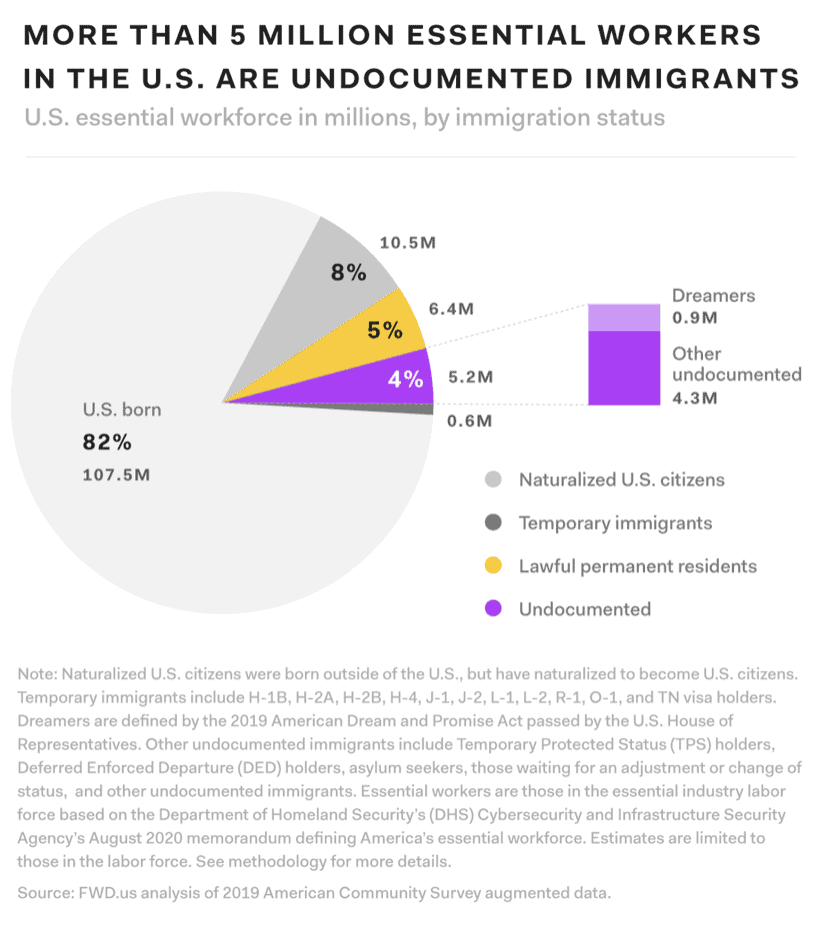

By The Numbers: Essential Undocumented Workers

- The percentage of undocumented essential workers exceeds that of native-born essential workers by nine percentage points in the 15 states with the largest labor force.

- In the ten largest metropolitan statistical areas, the percentages of undocumented workers exceed the percentage of native-born essential workers by 12 percent.

- A total of 6.2 million essential workers are not eligible for relief payments under the CARES Act.

Daniel works with a false social security number, paying taxes but not benefitting from a tax return, unemployment, or other benefits. He says, “The government should provide more support (due to the pandemic) since the money paid in taxes is much, and there is never a return because we (undocumented immigrants) do not have legal papers.”

A Center for American Progress analysis finds that undocumented workers and their households pay $79.7 billion in federal contributions and $41 billion in state and local taxes each year. In addition, from 2010-2019, undocumented workers paid $13 billion in unemployment insurance taxes, reports the Fiscal Policy Institute.

“They (government) don’t care if you’re legal to collect taxes, but they do to give aid,” says Guadalupe. She and her husband, Erik, are undocumented immigrants with two daughters born in the United States. Both asked that their last names not be used due to their immigration status.

Erik, the sole financial provider, distributed vegetables and fruits to supermarkets. The family was fearful of not paying expenses like rent and utilities during the pandemic lockdown. Gratefully, Guadalupe says the family received some assistance. “We were able to receive food aid from a local church. It gave us a feeling of protection; it minimized our worries because we knew that our daughters would not starve.”

Immigrant rights advocates argue the lack of resources afforded to undocumented immigrants during the pandemic stems from former president Donald Trump’s four-year hard stance on immigration reform including baseless rhetoric that they are “stealing Americans’ jobs.”

A Pew Research Center study found that when it comes to undocumented immigrants, about three-quarters of American adults (77 percent) say they mostly fill jobs U.S. citizens do not want.

Essential undocumented workers make up nearly 1 in 20 essential American workers, with millions working in construction, food services, production (including agriculture), transportation, healthcare, and other vital industries.

“We are visible for what they need us; essential, but when they exclude us (from getting aid) – they make us invisible in this country,” says Guadalupe.

Cover Photo Credit: John Guira

Publisher’s Note: According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Hispanic-Latinos are nearly 4 percent of the New Hampshire population and 2.3 percent of the COVID-19 deaths.

Yamila Martinez is one of six fellows in the Journalism Camp: Covering Race, Ethnicity, and Culture sponsored by the Hortencia Zavala Foundation (HZF). The first-in-class free 12-week program led by the Owner/Publisher of the Latino News Network and twice president of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists (NAHJ), Hugo Balta provides practical guidelines for fair and accurate storytelling.

Martinez enjoys working with the community, especially the immigrant community in America. “I believe that every human has a story of success, failures, learning, and regrets,” she says. “I like to bring out stories to the public and contribute to making our society fairer.”